I am interested in sharing the topic of tonal regions; in this case, we will apply it to one of my own compositions for solo piano. In his book Structural Functions of Harmony, the notable composer Arnold Schoenberg shows that there is, in fact, no real change of key in a composition unless the modulation to the new key lasts for a considerable amount of time or for the remainder of the musical piece.

The author suggests that one can move through different tonal regions, some closer to others, according to this “map”:

The piece discussed can be listened to below:

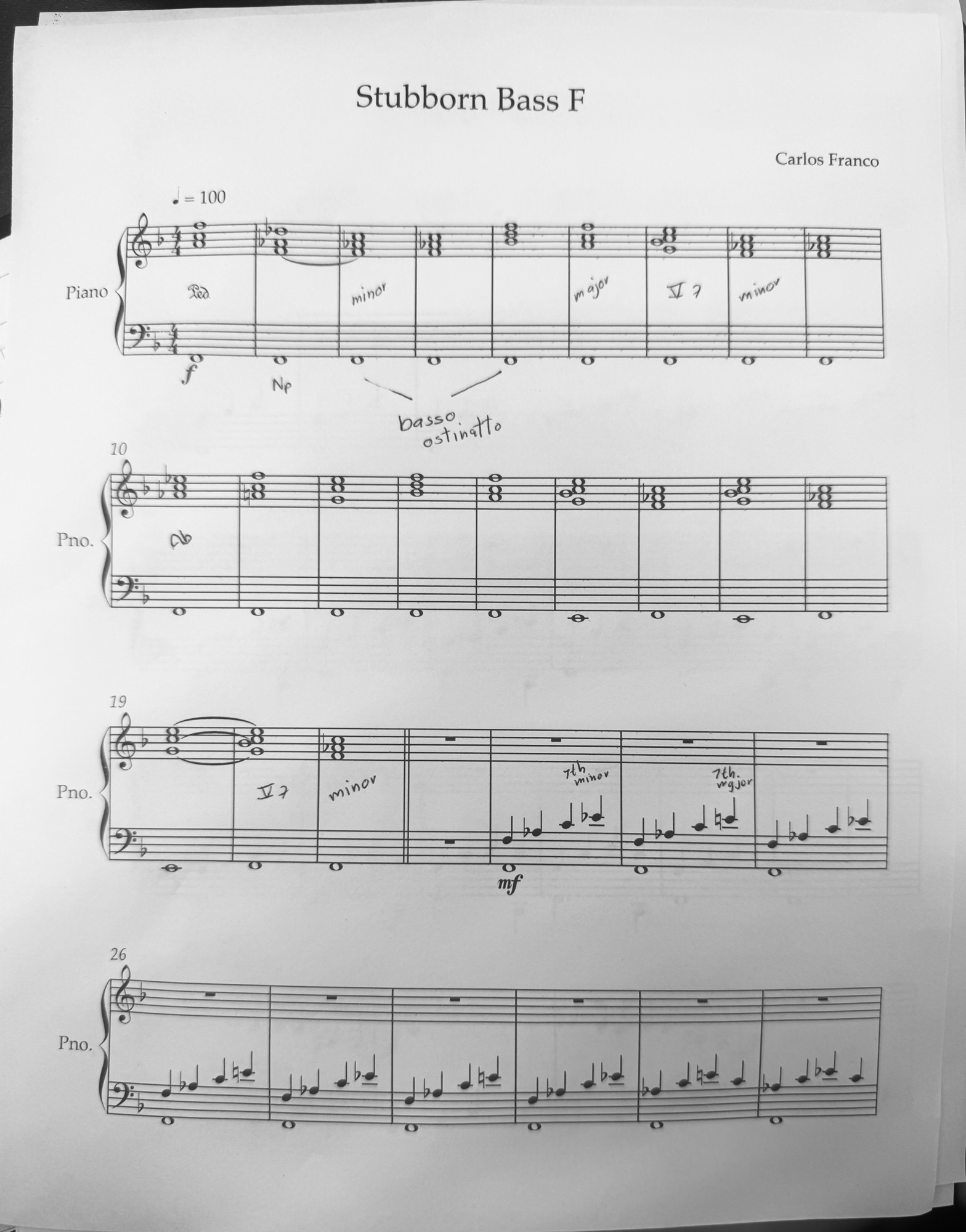

In that piece we have a constant feature: the ostinato bass on F in the left hand of the piano. From there, we can observe the following as shown in the score:

As we can see in the third measure, the piece falls into F minor through a Neapolitan sixth (Np6) in the second measure. In the sixth measure, F returns without much announcement, and through the C7 (V7) it modulates back to minor in the eighth measure.

Then, in measure 10, Ab appears as another chord of the key that would originally be F minor, which somehow establishes itself by resolving in measures 20 and 21 with a V7–I cadence of C7–Fm.

In measure 23 begins the second part of the piece, where several arpeggios are played while maintaining the continuo bass on the note F, at times emphasizing its fifth to give some variation to the left hand. In this second part of the piece, there is no real change of region except for the seventh, which alternates between major and minor (E and Eb, respectively, in measures 23 and 24).

The third part of the piece belongs to a genre that has always played with minor melodies and major accompaniments: the Blues. If we look at blues pieces, the famous “blue note” is nothing more than the minor third and minor seventh of a major key, and this is what gives the genre its distinctive character.

Finally, we leave the score here in case any reader wishes to try it out in their free time; it is extremely simple: