Following, as an exercise, the techniques proposed by Gonzalo Macías in “Doce maneras de Abordar la Composición Musical”, we move on to number 4. In his book, Dr. Macías discusses superimposing ternary rhythms against binary ones.

The Mexican composer’s method is very interesting; it is even worth examining how he subdivides measures based on the smallest rhythmic unit. This appears in Chapter IV of his book.

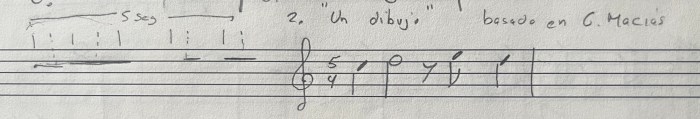

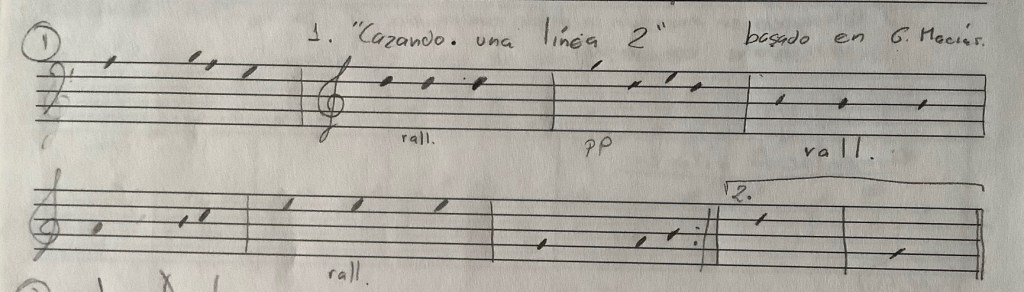

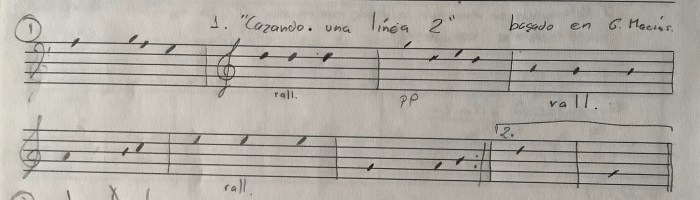

In our case, we decided to follow an approach closer to what we are familiar with and chose to write a piece for two instruments: piano and bass. Each instrument carries one of the suggested rhythms: the piano is responsible for the sixteenth-note groupings, while the bass carries a melody built on triplets.

For more information, the reader may consult the score here:

The final result was documented in a performance by the author in this video:

Four against Three

The piece is in C Lydian mode and closes in C major. The idea was to present the rhythmic relationship mentioned above, with a short interlude that plays with inversions of C major and D.