A harmonic interval is the distance between two notes sounded at the same time. These intervals shape how harmony feels, from rest and stability to tension and movement.

Consonant intervals sound stable and resolved. They blend smoothly and are commonly used to build harmony:

- Unison

- Octave

- Perfect fifth

- Perfect fourth (depending on context)

- Major and minor thirds

- Major and minor sixths

Dissonant intervals create tension and instability, often calling for resolution:

- Minor and major seconds

- Tritone

- Minor and major sevenths

Consonance and dissonance work together. Without dissonance, music lacks motion; without consonance, it lacks rest. Their balance is what gives harmony its expressive power.

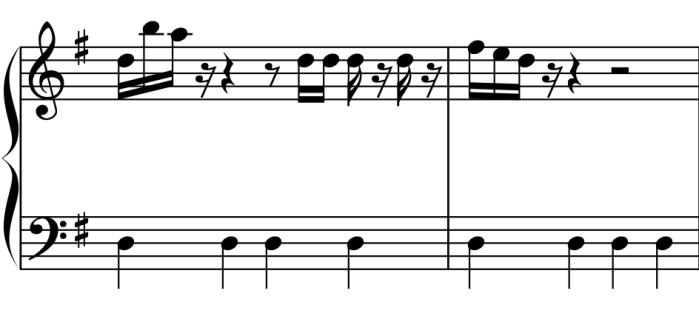

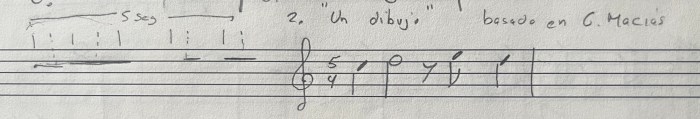

The following track, seeks to explore the different harmonic intervals and how they relate using a basic theme that appears all over the piece. Take a look at the music:

Each time the theme shows up, a new interval is used. The different basic intervals found on the major scale are used. The reader is invited to listen to the track:

The consonant intervals can be easily distiguished from the dissonant ones. The latter appear on measures 25 to 30. In measure 32 we go back to the stable thirds to approach the ending by slowing down the tempo and resolve in a traditional leading tone-octave cadence.